It is that time of the year, when we wear our tricolor with pride, listen to songs of valor, celebrate the contributions of our freedom fighters, and sometimes diss the pace of our country’s growth over the past 77 years.

Love it or hate it, being an Indian is our only identity on the world map. Today, let us look beyond the geo-political impact of India’s Tryst with Destiny at the stroke of midnight on 15th August 1947. To understand the true impact of India’s 150+ years and beyond, it’s time to turn the pages beyond India Before and After Gandhi.

Here is a list of reads that will mellow down the jingoism (or lack of it) to make way for you to realize the true meaning of what India really went through over all these trying decades.

- This India (Sheila Dhar, 1973)

Essentially a children’s book, This India is perhaps the most lucid narration of what it is like to truly ‘feel’ Indian. Commissioned by the Govt of India to celebrate ‘the 25th anniversary of the Indian Republic’, I discovered this priceless gem in the rapid reading section of my class 10th English textbook. I eventually held the original print, after 15+ years of searching. The book beautifully explains the concept of Indian culture and the Indian way of life. When I left home to live in another city in the country was the time I truly understood the emotional depth that this book offers.

Being Indian is beyond sporting a flag on our window. It is rooted in your very being; try as you may, but you still can’t wish it away. But you don’t have to be bitter to accept it. Every country, state, city, town, and village has its flaws, you will never find anything living up to the standards you experienced or expected. What you have is a beautiful symphony of life, and this book will give you the desire to make a positive change to the place you call home, sans the drama.

- The Princes: A Novel (Manohar Malgonkar, 1963)

Manohar Malgonkar is perhaps the most celebrated novelist of post-independent India. Royalty himself, I discovered Malgonkar’s witty historical fiction with political undertones as part of my MA English syllabus appreciating Indian literature. The Malgonkars were as good as the rulers of Dewas (located near Belagavi) and this book highlights his retelling of royal households closely.

A little history is needed to understand why this book is so essential to decipher the turmoil of India’s freedom struggle, being a country fraught with rulers throughout its existence. The East India Company ventured into Indian soil, masquerading as traders for spices and indigo. Now, for the royalty of India (mostly the Marathas, Nizams, Mughals, Maharajas, etc) English was an alien language that had no real need. With the help of middlemen, they built trading relations with the Englishmen. Slowly, they were encouraged to send young princes to England with the promise of superior education and a better understanding of the world’s ways. What that resulted in was a paradigm shift in thinking and behaving from the close-fisted governance in their provinces. In a rose-tinted world of shallow equality and equity, monarchy can stick out as a sore thumb, even in your own backyard.

Set in 1938 India, The Princes explores the life of Abhayraj, the heir of Maharaj Hiroji, the ruler of the fictional princely state of Begwad, as the Brit regime fades out. It is an intricate commentary of idealism, and ideologies, and offers a stark distinction on the generation gap, amplified by wars and political turmoil. An unusual historical saga of its times, you cannot help but pick sides. It is a fascinating and intimate glimpse into life in India’s princely states, as the country struggles to embrace democracy.

When you turn the pages, and read the words, you may find it alienating. Remember how ‘Dil Dhadakne Do’ or ‘Gehraiyan’ was about rich-people-problems? But strip the royalty, and you will soon realize it is the story in every household, where the kids were encouraged (or chose to explore) greener pastures in foreign lands. If you are someone who left home, chasing a dream or a degree, do you remember how you longed for things to be less dogmatic at home? Now, you’ve managed to change the way of life in your house, but some people are trying to leave you penniless and powerless. How would you face that battle? That is precisely what this book explores.

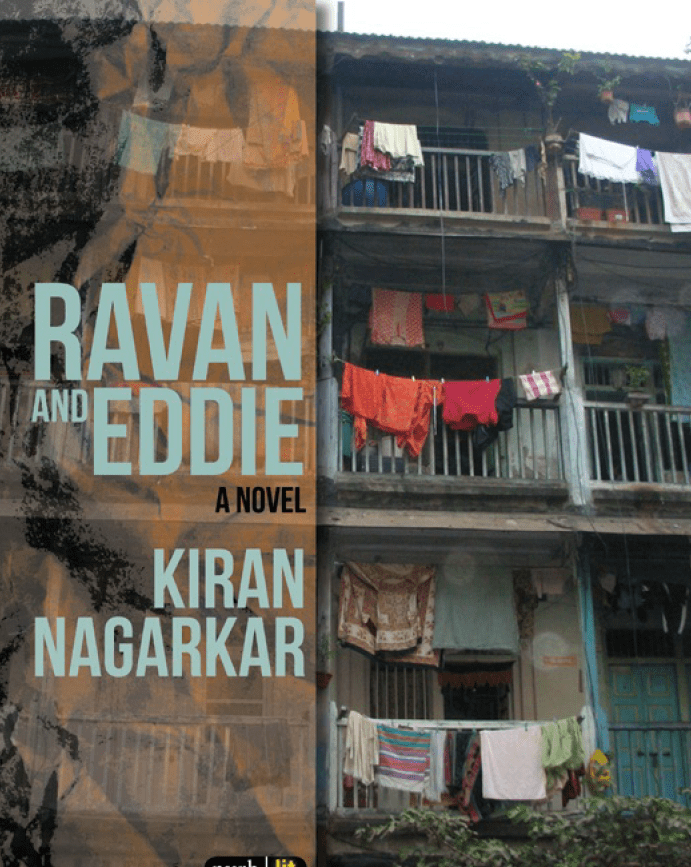

- Ravan And Eddie (Kiran Nagarkar, 1994)

Kiran Nagarkar is one of the best contemporary Indian writers I have ever come across. With his witty writing, he often broke conventionalism as a means to warn against the dangers of jingoism, not to confuse half-truths with reality. His sharp critique against right-wing politics often drew the ire of the party and left non-biased readers in splits. I wasn’t aware of this aspect of his personal life until a foot-in-the-mouth moment made it glaringly obvious.

In one particular phase of my life, I ended up, quite unwittingly, at a right-wing conference. As the leader dozed off on stage, my Kindle came to my rescue. As I muffled my laughs, a petit lady asked me what I found so amusing and I mentioned the title and author, just to see her face fall. But I digress. How, do you ask, is this book remotely connected to India’s Independence?

The story starts with the first Christmas of independent India and follows the path of two boys, Ravan (born Ram) and Eddie, and the simmering communal differences in Bombay City. If you have seen this brilliant 1977 masterpiece Amar Akbar Anthony, (yes, the one where the three sons have a live blood transfusion session for their unbeknownst mother in real time!), there was a Bollywood template that ruled the 70s and 80s cinema. The Christian family was thriving, united, and always loaded. Food was always in abundance and on a platter. The Hindu/Muslim kid is from a broken home, looking for solace in their Christian brethren. The Hindu is always, righteous, Muslims pious, and Sikhs benevolent. In these communities, poor men were heroes, rich were patriarchial maniacs and villainous. This was a stereotype that every movie reinforced for an excruciatingly long time. Nagarkar reversed roles, much to the annoyance of all communities involved.

In the first part of this brilliant trilogy, we revel in the characters of Central Works Department Chawl No. 17 in a nondescript part of erstwhile Bombay. For someone who grew up in this maximum city, I found each of them relatable, their woes real and captivating. As I read, through the connection of the voluptuous-yet-oblivious Parvati Pawar, drooling-yet-henpecked Victor Coutinho, his ever-jealous-and-all-knowing wife Violet, his tattletale daughter Pieta, the uselessly unemployed Shankar-Rao (he was a mill worker) and forever at loggerheads Ravan and Eddie are the most fluid people, wading through communal discord, living the most normal lives you’d ever see. None of them know why they are in each other’s crosshairs, and as a reader, I couldn’t pick a side right until the end.

There is one episode in the book involving a rabid dog and the helplessness that follows when it goes on a rampage. As the scene unfolds, you are reminded of an obvious class divide, and how this was a time in the country when mindsets had started to shift. It reminded me of Atticus Finch from Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird, but unlike the lawyer who defied norms to do what was right over what was acceptable, we as a nation were even hesitant to make the first move. We surely have improved a lot from 1994 to now.

Seldom would you find a male writer exploring emotions so delicately. There is one part of the book where Pieta tattles on Eddie and the way Nagarkar explores his emotional thoughts is hard to describe. I don’t know about freedom, casteism, left-right, or any other ideologies, but that moment gave me a profound realization. Bear in mind, I chanced upon this beauty of a book when I was on the brink of 30. I could finally comprehend how my brother felt, considering how much effort he needs to express his feelings.

In the age of social media, nothing in this book will come as a surprise. But don’t forget the year in which Nagarkar built his story. He was way ahead of his times and his observation, though diluted over the years in modern India, continues to ring true.

- Dongri to Dubai: Six Decades of the Mumbai Mafia (Hussain Zaidi, 2012)

While we are now on the topic of Mumbai, one of the most intriguing topics for me is the Mafia. If you grew up in the 90s, ‘Guns n’ Roses’ is an apt way to describe life in the ever-swelling city of dreams. While the book, Zaidi’s magnum opus, is dominated by the journey of Dawood Ibrahim Kaskar, it is so much more than that.

It gives you a detailed history of the evolution of the infamous Mumbai mafia, right from 1947, without sounding like a college textbook. From the Rampuri to the contraband industry that thrived, as the country went through long periods of unrest, has been an eye-opener. Like the Sicilian by Mario Puzo, Zaidi continues the saga in his follow-up book, Byculla to Bangkok.

Flowing like a bloodied river, at times it is hard to remember that it is not a work of fiction: these were living and growing up with us all along. As I closed the book, I, for one, was grateful to be oblivious to all this chaos and was left with a profound sense of gratitude to the law and order maintained in this wonderous city I call home. You really have to read it to believe it!

- Honorary mentions

This list will be incomplete without some of the most popular titles that deal with tales of partition and the aftermath of 15th August 1947. A few I have read, are here:

Train To Pakistan (Khushwant Singh, 1956)

I had the privilege to read the debut novel of the well-renowned Khushwant Singh at two different phases of life, and it left me disappointed on both occasions for entirely different reasons. Almost two decades ago, in my first year of graduation, I was tasked with writing a review of the book. As I look back, I now realize how shortsighted an 18-year-old can be. My prejudices and lack of worldly knowledge showed in my Puritan point of view. A decade later, when a lot of life happened to me, I could appreciate the grays of the world. But what left me longing for more was the disconnected narrative and the untold endings of so many subplots. It didn’t work for me, but the saga of love, betrayal, and ultimate sacrifice may work for you.

A Suitable Boy (Vikram Seth, 1993)

Dubbed one of the longest literary marvels from India (at a mammoth 1400 pages), the book revolves around the aspirations of the affluent class and the shift of ideologies in the post-colonial era. It requires a lot of commitment to live through the maze of four families over 18 months: the Mehras, the Kapoors, the Chatterjis and the Khans.

It explores political prejudice, social conflict, changes in racial norms, sporadic episodes of violence, and inter-generational connectedness. It also explores the true meaning of love and the institution of marriage, which is sacred and often an unavoidable standard in India. Over the years, my feelings towards all women in the narrative have shifted drastically, as age and experience take over. It is like a fine wine that ages with you, and you understand the perspectives and actions of each character with grace.

Short Stories on Partition (Saadat Hasan Manto)

I cannot write on a topic so heavy, without an ode to Manto. Born in India, with roots in Kashmir, Manto was no stranger to the literary world of Bombay and Delhi before 1947. In 1948, he moved to Pakistan, shaken by the communal violence and horrors of partition. His story stories are not for the fainthearted and bring to the fore the cruel human nature in the face of turmoil and adversity. It is hard to pinpoint which story is most terrifying of them all. But ‘The Dog of Tetwal’ shook me the most. In the face of blind jingoism and misplaced ideologies, no one is safe, not even your beloved dog! When a man is filled with hatred and blinded by a shallow sense of morality and supremacy, no low is too low in the free fall from grace.

The Shadow Lines (Amitav Ghosh, 1988)

One of the few books that explore life over a period from 1938 to the 1960s about the Bengali diaspora, it is not just a story. It is a narrative that talks about people’s experiences in a non-linear format and jumps from imagination to reality. In doing so, Ghosh invites us to be a part of the story and leaves it to our interpretation. Jumping from the Swadeshi movement, the Second World War, the Partition of India, and the Communal riots of 1963-64 in Dhaka and Calcutta. It also dwells on more sensitive topics like the weight of immigration, expectations of a good life, longing for what was left behind, bullying in a foreign land, finding love, the price one pays for their stubbornness, and eventually the ultimate sacrifice in the face of tragedy.

Which books have you read on this thread? Is there anything you want us to explore? Do share your thoughts in the comments.

Beautifully written ma’am, while reading I felt like I’m actually listening to you, as we used to in your lectures.

LikeLike

That is so Kind of you! I cant believe after all these years, you still remember my classes 🙂

LikeLike